- Home

- James Gregor

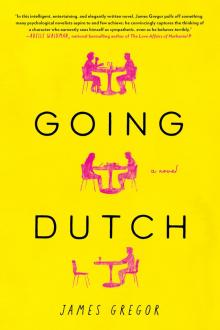

Going Dutch Page 2

Going Dutch Read online

Page 2

“Did the auditions go well?”

“I think so. One of them brought back some funny memories.”

They passed a small outdoor café, fluttering with activity, and Blake related an anecdote from his adolescence, something about a hunky chemistry teacher and a narrowly avoided scandal. As he did so, Richard fished in his memory for an experience of his own that might appeal to Blake. He considered relating his first encounter with Ayn Rand: reading the slim fable Anthem in high school English class one day, while the rest of the students worked through The Catcher in the Rye, but decided against it when he realized that Blake was talking about his relationship with his parents.

They hadn’t helped him realize he was gay; he’d spent his late teens and early twenties in a “sexual darkness.”

“My twenties were sexually dark too,” Richard said.

Blake smiled.

“But it’s gotten much better,” Blake continued. “I think they were just confused. They’ve come around a lot in the last few years. I’m lucky. Now they’re supportive.”

Blake began talking about dating girls in college. Richard looked over the railing toward the miscellany of buildings that flocked to this part of the island—some billowed, some pierced; it was a playground for famous architects. A group of guys, laboriously tanned and muscled, moved down the street, chatting loudly and gesturing in broad, confident whorls. Richard didn’t have a “group of friends,” only ornery but devoted individuals in a variety of pursuits—teaching English in foreign capitals, learning violin making, studying yoga on a banana plantation—and he envied those who seemed to belong to a unified pod that spread itself five abreast on the sidewalk, sharing gossip. As it was, the majority of his friends were too indebted to afford gym memberships, though some among them managed to wrangle free Bikram yoga classes in exchange for washing the floor after all the sweaty bodies had lifted off.

Blake touched his hand.

“Hey, what’s so interesting over there?”

“Nothing. Sorry. Want to have dinner?” Take me out for dinner, Richard meant. He’d finished the last of the Raisin Bran in the middle of the night, munching tactfully at the dark kitchen counter while his roommate, Leslie, snored on the nearby sofa. The cupboard was empty now. But Richard knew that Blake was unlikely to come through. Going dutch was, not just between two men, but among everybody now, the norm.

“Somewhere around here?”

“Sure,” Richard said. “I’m easy.”

A yolky suggestion of ozone blanketed New Jersey, couples drifted past holding hands, and tourists took pictures of the big concrete hotel.

“What kind of food do you like?”

“I have eclectic tastes,” Richard said, resolved to seem as open-minded as possible, and not wanting to bracket off any potential dinner opportunities with Blake.

“My friend is a sous-chef at a place in my neighborhood,” Blake said. “He said he’d get me pan-roasted fluke at a discount.”

Richard was hopeful again.

“But I don’t know if he could do it for two. I’d pick somewhere cheaper”—Blake smiled compassionately, tilting his head—“but I really need to eat something decent tonight.”

Richard nodded. “I understand.”

They went down a flight of stairs to street level. Richard followed behind Blake, eyes on the black sickle of his hairline, the tag of his cardigan erect against the green collar of his oxford shirt. These dates always failed. It was a predictable script: a few hours of milky diplomacy, siblings and sleep patterns and diet touched on, before parting ways with a hug that was not exactly disingenuous but certainly performed, as if wishing each other courage in the next phase of the battle, which was the continued search for love, later to ignore each other in public if they ever crossed paths again. Then back to his apartment, back to sitting cross-legged on the bed with his laptop and a tub of lime sorbet, trying to view his life in a positive light.

“Actually, I think I know a place,” Richard said.

They stood on the corner, facing each other, about to part.

“What kind of place?” Blake asked, perking up skeptically.

“It’s not pan-roasted fluke, but it’s good.”

Blake thought for a second, then said: “Okay.”

Buoyed by this successful maneuver and the temporary rescue of the date, Richard led Blake south down a sidewalk thronged with dog-walking couples. No one knows that we just met, Richard thought. We could be in a long-term relationship. Any one of these people might think that Blake had chosen me from among the countless eligible young men of New York City.

Richard wanted to belong to that group of young men who were chosen.

When they arrived at the restaurant, Blake peered through the window as if into a condemned building. “What’s an egg cream again?” he asked, climbing into the booth.

Did this mean Blake was a recent arrival to New York, lacking that period knowledge? He’d been evasive when Richard asked him how long he’d lived in the city. People could be so touchy about that question.

“It’s milk and syrup added to carbonated water,” Richard said.

“What are you getting?”

“The garden salad or the Caesar salad,” Richard said, scanning for something cheap. “Probably the garden salad. You get whatever you want.”

“You’re going to make me fat and happy.”

When the waiter came over, Blake ordered the shrimp Scampi. It was three times the price of the salad. Richard was someone who never ordered a dish more expensive than the host’s, even when exhorted to do so. At the same time there was something agreeably carnal about Blake’s shameless appetite.

“Eating is a very cerebral and academic experience for me,” Blake said after the waiter left. “I love to think about food connected to history, psychology, sex, and gender . . .”

“So, when you eat a hot dog . . .” Richard said.

“Hot dogs? Hell no,” Blake said. “Do you know what’s in them?”

“Okay, fine,” Richard said. “Veggie, wheat burger, whatever. You’re besieged by the linguistic, historical, religious, etcetera of the burger.”

“Okay, you have been listening,” Blake considered, with a smile.

“What about just, you know, a taste sensation?”

They bantered in this vein for a while, until the food arrived. Blake glared at his dish—a morass of oily threads under a squall of Parmesan cheese.

“I’m blaming you if I get sick,” he said.

“I’ll nurse you.”

“You better.”

Richard’s salad went quickly, and for several minutes he tried not to watch Blake consume the shrimp.

“Are you watching me eat?”

“Sorry,” Richard said, taking a sip of water, which he’d been nervously doing ever since they arrived. Now he needed the bathroom. He excused himself, and as he made his way across the diner, peopled by a mix of old ladies, dissipated rent-controlled locals, and nostalgia-oriented transplants like himself, he wondered if Blake was husband material. His LAST ONLINE always indicated a reasonable time of day, unlike the majority of profiles, which, especially on those weekends Richard came home in the middle of the night, were usually active at some desolate hour: 2:46 a.m., 3:57 a.m., 4:21 a.m. Richard imagined the owners of the profiles in their bedrooms, lonely insomniacs, their frustrated return home from yet another disappointing night out; waiting alone with a collapsing buzz on the grimy subway ledge for the train that wouldn’t come; the pitiless white light in the cars that decelerated frequently between stations; the walk home at the end of the journey through dark and empty streets.

He imagined Blake pulling an elegant maneuver and paying for the meal—standing there beside the booth when he returned, as though to assist Richard with his coat, not meeting Richard’s eyes because he wouldn’t want to draw attention to the payment, with a glimmer of demure masculine capability in his expression.

But the bill was still there

when Richard got back, and Blake was staring out the window at two muscular men in tight V-neck T-shirts—tempting the still fickle spring weather—who were walking arm in arm. For such a supposedly solitary city, where everyone either was a lonely neurotic who lived with a dog, or blew most of their paycheck on therapy, analysis, or rent, New York could at times feel as if it was the exclusive domain of couples. And children. Every day there were more children.

Richard took out his wallet, trying to mask his disappointment with chivalry.

“Only a five-dollar tip? I thought the waiter was a nice old guy.”

“I just think tipping is getting a little out of hand though, you know?” Richard was flustered by Blake’s insinuation of cheapness. “It seems like every six months it goes up by, like, five percent.”

“Shitty job though.”

They left the diner and soon reached a basketball court surrounded by a fence. Sweaty men moved back and forth over the artificial ground. Richard was unsettled by what had just happened. So was Blake just rigorously egalitarian in his dating practices? As the sky began its parabolic exit, he imagined their future together as a scrupulously calibrated transaction of equals, a continual updating and canceling of accounts, until the ledger effaced itself.

These moments, as the next stage of the date was decided, were always filled with pressurized speculation. Richard glanced at Blake out of the corner of his eye. He at least wanted the entanglement of their arms, the cozy liaison of an easy silence, to walk along the Hudson with him, serene in the high-strung city. He didn’t want to go back to his apartment alone.

“It’s such a nice night,” he said, looking up at the pink clouds and risking an optimistic note.

“I hope your nice night continues,” Blake said.

“Are you leaving?”

Blake nodded, and Richard’s heart—whatever it was that could sink—sank.

“Well, we should do this again sometime.”

“I have your number,” Blake said.

“You should use it.”

Blake leaned in and kissed him on the cheek.

“Ciao!”

Richard watched as Blake hurried down the street and disappeared around a corner. For a moment, he stared at the empty intersection. A truck careened through.

So that was it? Another extended hand left hanging in midair, but no overcoming of particularities, no conquering of idiosyncrasies, no alliance made? He turned and started walking toward the subway.

On the ride home, in the intimate scrimmage of the shaking car, his sense of loneliness was alternately charged and deflated, belittled and aggrandized, by the presence of so many other people. A homeless man snored at the other end of the car, a nebula of smell keeping others away. A child ate a chocolate bar with a hypnotic expression, his mother’s eyes red from crying. Richard felt a shivering sense of defeat at what he was going back to: the dark apartment, the ziggurat of plates in the sink, his faraway roommate, Leslie, on the couch, the empty bed. It seemed foolish and unjust to be moving in that direction, when Blake was maneuvering through the streets behind him, drawn somewhere else, free again, set loose in the potential and marvel of the city.

TWO

Richard went back to campus the next day. Calmly lit by muted sunlight, all throughout the library people seemed to be making great progress with whatever they were doing. Richard sat in one of the glazed wooden chairs, his thoughts crawling. He was supposed to be writing about Pier delle Vigne, the Sicilian court poet whose suicide had inspired Dante to transform him into a bleeding tree in Canto XIII of Inferno. But hadn’t the great Austrian philologist Leo Spitzer said everything there was to say about that?

Richard clicked open the homepage of the New York Times. He checked the weather, and the price of a pair of sneakers. He dragged the throbbing cursor indolently back and forth across the glowing screen.

He decided to go back to Brooklyn and try working there.

As he walked down Broadway toward the subway, Richard spotted another doctoral student from the department up ahead. Her name was Anne and she was standing beside a table of ratty used books, lorded over by a man with Coke-bottle glasses and a gray ponytail. She had on sturdy tweed pants and a shapeless maroon sweater, and she wore large, circular black sunglasses.

Looking for an escape, Richard slowed his pace. Anne, also a PhD candidate in medieval literature, but with a slightly different focus, had been inviting him to lunch ever since they’d discussed collaborating on a paper a few weeks back. The initial gesture had been Richard’s, when they’d spoken at a departmental wine and cheese, bonding sarcastically over a hole in the wall and the general disrepair of the facilities.

“I thought this university was supposed to be well endowed,” she’d said, giving him a preposterous heavy-lidded wink.

Painful joke aside, Anne was well known for her ferocious intellect and Richard had been struck by the idea that a professional association with her might resuscitate his sputtering academic career. She was always publishing in the most prestigious journals—if it was still possible to call those types of journals prestigious—and there had recently been a call to submit papers for a conference taking place in Montreal. Coauthoring would be easy: her interests were close to his own, only substantially more radical and compelling.

But the routine was getting expensive. Numerous times over the past month he’d found himself sitting across from her at exorbitant restaurants in various parts of the city—though mostly on the Upper East Side (they took cabs there), where she’d spent part of her childhood. The restaurants were often checker-floored, and traversed by haughty waiters in tuxedo collars. Swept up in farm-to-table and other Brooklyn-centered dining trends, to the degree that he could afford to be swept up in them, Richard had all but forgotten that these formal white-tablecloth restaurants existed. Barely able to afford anything and feeling underdressed, he often ordered only a single bottle of Perrier. Sometimes the waiters would glare down at him as if they considered this an outrage.

The last time Anne had invited him to lunch, he’d accepted but then blown her off an hour before for a Grindr rendezvous.

A FRIEND IS IN CRISIS, he’d texted.

I HOPE EVERYTHING IS OKAY, she’d replied. LET ME KNOW.

Afterward, feeling an unexpected swell of guilt, he’d gone into an overly elaborate description of this phantom crisis, then asked to see her again as soon as she was free.

Part of him found her annoying; another part was curious to observe her. There was something both needling and captivating about her that he couldn’t explain. The other week, he’d gone to watch her teach a class. Before an audience of callow undergraduates, she transformed, emitting waves of musky, indeterminately foreign glamour. Gesturing wildly under a forest-green cape, she expounded on the book the students had been assigned; then, pacing from one end of the cramped room to the other, she digressed on the subject of humility, a trait she clearly felt most of the students lacked. She wore bangles on her wrist that made a punitive rattling noise. For misusing the term “stream of consciousness” in an oral presentation, she lambasted a young girl.

Richard found himself strangely excited by her presence in the classroom. It wasn’t attraction exactly, but he felt the blurred outlines of that category. The possibility that she would address his discernible but unacknowledged sexuality played a part in it. This potential disclosure—of something both laughably obvious and titillatingly ignored—gave their interactions a weird and alluring sense of pressure. She was stubborn and bullish in her feeling, ignoring all signs of potential failure, but this sprang from a mind that was impressively retentive and refined.

Was Richard scared of genuinely becoming attracted to her? She wasn’t even pretty, and he was gay. But then, his heroic dedication to the male body—all of his screensavers were Mapplethorpes, for instance—and his rigid indifference to the female body, had begun to seem passé. Once a kind of calling card, the fact that he was attracted to men wasn’t par

ticularly novel anymore. Yet it was men he was attracted to; masc men if he was being honest, though he knew that was deemed problematic. Still, for reasons unclear to him he’d felt unable to rebuff or even to clarify her overtures.

He turned down 109th Street.

“Are you trying to avoid me?” Anne called out to him. “Sometimes I run after people when they do that.”

“Of course not,” he said, trying, by an abrupt torquing movement of the head, to make it look as though he hadn’t seen her.

“I’m buying a Russian dictionary.” She walked over and showed it to him. “There’s no point reading Anna Akhmatova in translation.”

“Ah.”

He was distracted by a muscular deliveryman lifting a FedEx box through a doorway.

“Come over for lunch,” she said. “I live nearby.”

“But you don’t cook.”

“Of course I do. I just prefer restaurants.”

They began walking, and Richard was incredulous. Was he actually going to her apartment? This was the height of absurdity. It was like the first time they’d spoken, on the way out of the Italian Department, during those sticky, thudding days at the beginning of the semester.

“I can’t believe not a single one of them has read Auerbach,” she’d said, complaining about a class she was TA-ing and stumbling to keep up with him—she was barely five feet tall, curvy and slightly plump, with a reddish, boyish pixie cut—as she gave a clotted group of smokers, gathered by the door to escape the rain, a nasty look. “You should read that before college, don’t you agree?”

He’d nodded more enthusiastically than he meant to.

“If you want to get anything out of your college experience, that is.”

As they crossed the harshly streaming traffic of Broadway, he glanced at her, sighing inaudibly. At least she wasn’t one of those medical or law students whom he always seemed to get stuck talking to at parties, or one of those calamitously thin hipsters who chewed his ear off about their boring critical theory papers. Why was he always transmitting signals he was unaware of?

Going Dutch

Going Dutch